mollysday (james joyce -ulysses -penelope)

a kind of film on molly bloom

by roberto freddi

Per verificare l’effetto che poteva avere il lavoro di uno ‘straniero’ su un pubblico di specialisti irlandesi, ho invitato alcuni devoti scholars di Joyce, riuniti in un’associazione a lui dedicata, a una visione del lavoro al 50% della sua lavorazione. Qui di seguito lo scambio di mail. Per facilità di consultazione, sottolineo in grassetto i passi più sintetici dei pareri, sia quelli positivi, sia quelli negativi. Ometto i cognomi per questione di privacy, ma è ovviamente tutto documentabile.

previews / reviews – for personal use only (pre-production)

…from some e-mails received after the first view of a draft of the movie (at 50%).

I am omitting last names… (author’s note: from now on ‘rf’ – roberto freddi)

“These are very rough draft notes made a few months ago. At the bottom of the email are a further six comments from different members of the group (a ‘joycean group’ nda). A very wide range of opinions. (…) But good art excites polarising views.

I think your work deserves a wider audience & I wish you well. We hope to be in Trieste for the Joyce Summer School 2020 & who knows we might meet you there! best wishes. Paul

MOLLYSDAY REVIEW by Paul …

My first reaction was excitement & pleasure at the change from the traditional format of a single female character usually face to camera or on stage in a monologue.

I like the way the different / differing voices weave in and out and around each other which for me is like a link to Penelope weaving / unweaving in order to delay the suitors & waiting for Odysseus.

Molly is a very complex, difficult and tough woman. She moves through a huge range of thoughts & emotions. Sometimes she can be blunt and aggressive – so I think we have to guess what is the emotion driving some of her outbursts – eg., jealousy, loneliness.

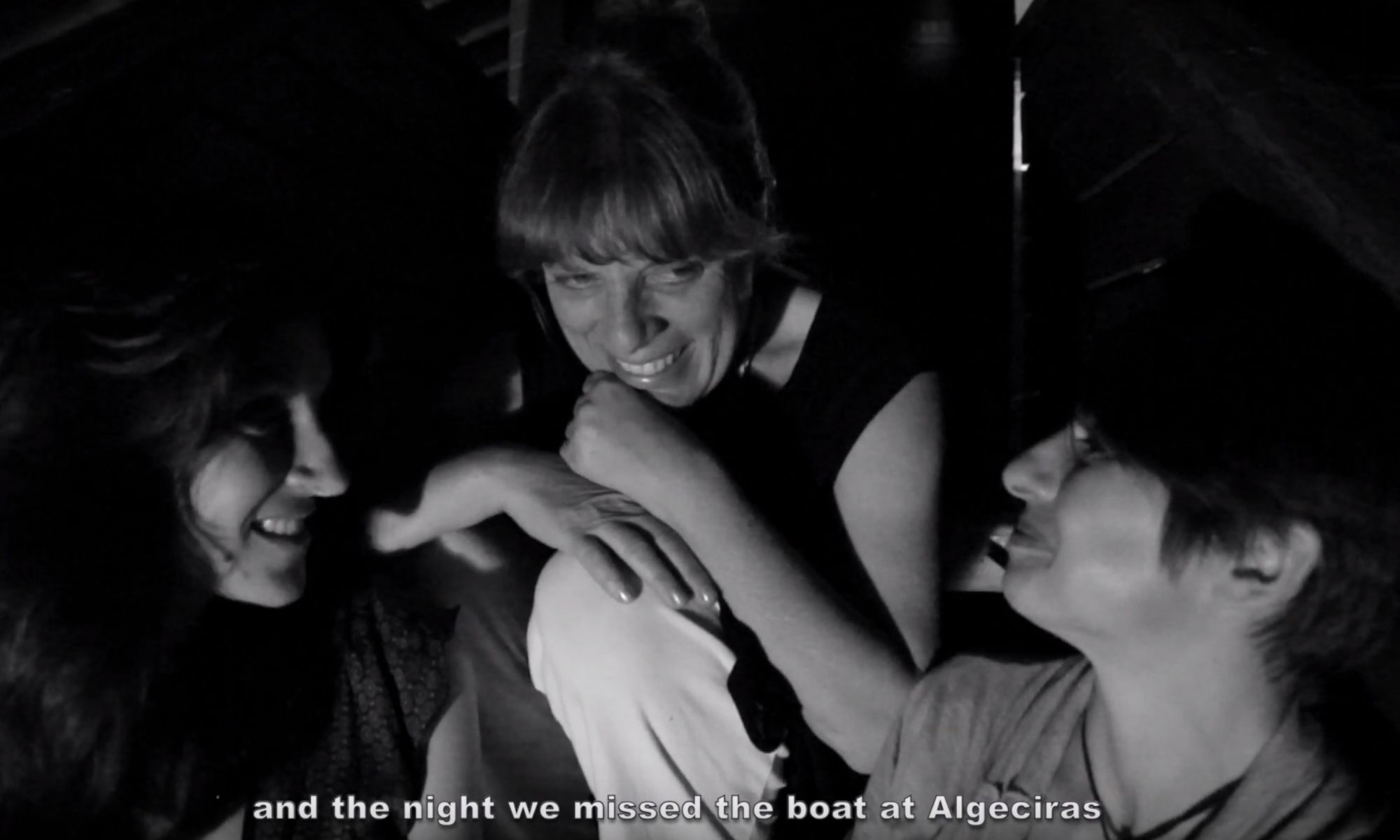

I like the mispronunciations and the moments of laughter which the actor finds hard to conceal because of the nature of the material.

I like the repetitions and the eye contact between the actors.

Introducing a male voice also challenges gendered thinking.

And of course, Molly is a womanly woman but I think it helps to get at the notion of animus/anima intrinsic bisexuality or the intrinsic masculine and feminine in both women and men.

The breastfeeding scenes call to mind the potentiality and therefore poignancy of the loss of Rudy. (This had (some) critics).

The fact that it is an extract – but a big extract – is a reminder of the density of the text and the enormous range of shifting emotions and thoughts.

(was there an omission /skipping of menstruation and pissing / shitting??)

I like the anachronistic contemporaneity of the settings

External conversations mirror internal conflicting thoughts / dialogues

Younger and older actors

The age range – emphasises the ‘universality’ (timelessness) of the piece/writing.

I liked the fade into colour at the end

– Are we emerging out of a dream or going into a dream –

– Is there a fleeting image of Stephen / Rudy in the colour section?

– Music at the end renders an edge of plangency – allows emotional release in the viewer

– It reads the text in a post-modern way – as is the polyvocal / fractured and deconstructed

– A good length at 1 hour

It is Molly as Everywoman – so it is also a reminder that she is not a Dubliner

Or modelled / mapped from a Galway ‘Nora Barnacle’

She is the daughter of Lunita Laredo who may or may not be Jewish – whose whereabouts are a mystery – to us the reader,

And who is also unavailable and unknown/unknowable to Molly as a ‘mother figure’.

Her father is ‘Major Tweedie’ who may or may not have been a ‘real’ major but more likely a ‘Sergeant-Major’. She is also an outsider in the Dublin scene – mirroring Bloom’s ‘otherness’ and ‘ousiderness’.

(Some of Blooms defensive rationalisations in Nausicaa are akin or analagous to Molly’s diatribes).

In the movie we have a range of ages of actors, which is very clever, eg with Boylan, we have a young woman in his ‘grip’.Is the breast-feeding imagery – part of a tradition of Catholic Iconography of the Virgin Mary? How does it fit? Does it belong?

When we read the soliloquy, we develop our own private imagery and we can go at a pace which stops and starts, moves smoothly or irregularly or fast then slow – sure or unsure – but deeply aware of the density of the text.

Which we could refer to as the ‘tissue’ of the text – Molly as tissue / flesh & blood and tangible and real – The film perhaps makes her more ethereal and ‘thematic’ thru’ fragmentation

an idea of woman / femaleness

Or feminity

She is a decentred Molly –

The film is a strong contrast with the familiar or usual approaches – of a single female voice – usually in a strong Dublin accent –

Does the film stand alone?

Yes, as a work about ‘female’ or ‘woman’s desire’

But it does float free of ‘Joyce’s Ulysses’ ?

Reading Penelope at the end of this dense text is quite different (obviously) than a movie of Penelope – (difficult to expand.) We the readers know

– that Bloom & Molly are inextricably bound up with each other –

– about Rudy’s death and its impact on the couple

– about Bloom’s father’s suicide

– about Milly being pushed out of the nest and ‘traduced’ by Bannon

– we know about Boylan

– and the jingle/jangle that haunts Bloom all day

So Chapter 18 is enmeshed in the preceding 17 chapters –

The film is a very different experience than the reading of the book

(this is the same for all movies, of course). Perhaps what’s unsettling is that we all have a definitive Molly in our mind’s eye and the movie disrupts that cosiness of ownership.

So it’s modern

Set in Rome (acually in Turin – rf)

Multiple voices

Male voice intrudes

Breast feeding baby

Incomplete

accented English

Other Responses

Maureen wrote…..

Hi everyone, I wondered if you would like to write a few lines summing up your reactions to the Molly’s Day film we watched last week. Paul and I said we’d give the Director and actors some feedback. Marj, I think your reaction is quite valuable criticism, which we will include as constructively as we can. But if you can find a few minutes, it would be interesting to see how it’s sat with you all since seeing it.

All best Maureen.

Kate…..

I would love to see the film again. It conveyed for me some of the breadth and energy of the text, although at times I found the editing a little choppy and therefore somewhat intrusive. Similarly with the pacing – more languorousness would have been welcome. Sorry this isn’t very specific – but I did say a second viewing would be welcome x

Molly’s day – from Marj…….

Maureen, Paul – thank you for inviting me to contribute despite my ungracious response when we watched the film. I don’t seem to be able to be critical about drama in a detached way but rather get cross as if it was a personal affront! I do have a good idea what this is about but not to the extent that I’ve resolved my issues. Anyway here goes.

It was an inspired choice for this group of Italian actors to perform Molly’s speech as a conversation but difficult to bring off. One of the things which makes Molly’s speech so vital are the quick shifts from reflective, sensuous to bawdy, bitchy, childlike, matter of fact. The film, despite the actual different voices remained within a narrow vocal range in pitch, pace and timbre. I thought at first they should listen to more Irish people in conversation but no – Italians use huge range – smokey, sexy, edgy, biting. So, for me it came across as bland, visually as well as aurally because since the thought processes didn’t have these gear changes neither did the facial expressions. On a purely technical level, one of the men, the one with the more-gravelly voice, seemed to be in a completely different space from the others – maybe just too close to the mic. It really made me want to go back to the speech and examine it- not that I’ve done that yet!

Tony

Pretty much agree with all this although, oddly, I still very much enjoyed it at the time. Despite the five (?) different women, I didn’t feel that the range of Molly’s emotional responses was sufficiently characterised. Also to have an actual man (too stylishly rumpled) detracted from Molly’s cynical perceptions …

But without looking closely for the text it was an engaging hour of film.

Was every actor credited?

In fact perhaps the stylish rumpledness is a fair analogy to Boylan’s swagger, but that in itself makes me wonder if it does translate to modern Italian bourgeois life. Some of Molly’s attitudes and preoccupations begin to feel more anachronistic than is entirely comfortable.

VAL

Just a few lines. I enjoyed the fact that several women spoke Molly’s lines. Gave a sense of universality and women sharing confidences and (at times) humour. I thought that a very different take on the soliloquy and added variety. I was a bit troubled by the male voice taking over at times though a silent male actor would have been fine as his manner illustrated her thoughts.

That’s all I can say for now. Two days of wedding celebrations have left me a bit addled. I was very glad if the opportunity to see the film. V xx

Maureen

I’ve already sent my thoughts but summarise and add bits here below

I think it’s a brilliant and very original way to do it. I loved the different voices and the knowing looks and giggles between the women.

I was quite shocked to hear men’s voices in it, initially. I can understand the reasoning though – especially in today’s more gender fluid times… since my first watching it, we have read this chapter in our group, with men reading parts in turn. It would have seemed very churlish to say that couldn’t happen and it certainly allowed them to explore their ‘inner Molly’, and it was entertaining and revealing to see/hear what that evoked in the group. But my first reaction was …. God, now we have men speaking Molly’s voice…. Is nothing sacred??

One pronunciation issue is ‘Howth’. We always have the same problem in our reading groups – people say HOWth – as in ‘how’ rather than ‘hoe’ (corrected; as immediately scheduled – rf). This sounded wrong to an Irish ear. However, the Italian accent in general – I have no problem with – in fact I rather like it and I believe the Italians are right in thinking they ‘own’ the book partially as it was written in Trieste (though then part of Austro-Hungarian Empire).

Following the ‘screening’ to our small group, I asked myself if I agreed with the criticism that there was a lack of range in the pitch and tone of the voices. I’m not convinced. I think Molly is too often played without enough emphasis on her sensuality and this marked a positive change of direction for me.

The other question in my mind was whether this was a ‘man’s’ view of Molly. But of course, Joyce’s view of Molly is a man’s view – so is this a useful line of inquiry? I’m not sure.

I wanted to add that I think the film would be well received in Dublin – for next year’s Bloomsday, it would be good to find a slot, either by liaising with the Joyce centre or the Italian Embassy who always have a big contribution to the day’s events. This would be a really fun thing to attend.

My (low) notes (Roberto Freddi)

Dear Maureen and Paul,

dear all of you that spent your time on this, thank you for your priceless attention.

All this is in order to share something with people that love literature as much as I do; this is the reason why I am putting together this work-in-progress, ‘mollysday’; work that is addressed to explore a different way to make profit of movie techniques in favour of literature – instead of the usual opposite direction.

As an experiment, the invitation was to post your comments on it as on a Baconian table of occurrences. Every positive or negative note or, better said, every presence or absence, will be applied with equal satisfaction to a matrix that is equally as yours as mine.

The spirit of exploring how ‘cinema’ (or theatre) can be beneficial to literature, is condensed in the last slot of the final credit titles, Plato’s conclusion, on behalf of all the others coming after that one – especially in the domains of Cognitivism, and most of all, contemporary Pragmatism.

In the first place, I wanted it to be watched not by ‘cinema people’, just because they are not the audience I would choose for that purpose. It is, for sure, to be potentially offered to a general audience, but I would preferably like to share it with people who live literature not just as a ‘different thing’ among others.

Please consider that I did not mean to explain Joyce to anybody – especially not to your circle!

In fact, this project is a little more about ‘Language’ than about ‘Joyce’.

Having said that, Joyce has been chosen among other ‘candidates’ for a couple of reasons: firstly, because of my long-life affection for his work. Secondly, because as a great author, he is simply a better element (remember the experimental vocation…) to process the question: “Is thinking an inner dialogue?”. Joyce is obviously a common resource, translated and cultivated worldwide, so it is easier to judge the results. Applied results, not for the mere love of research. Technology, not pure theory… And also for other similar reasons (Italy, internationality, exile, etc) I will not repeat now.

My present way of treating a text like that, ‘frame by frame’, comes, in all evidence, from far: biblical hermeneutics, for sure (Talmud, scholars of all kind), but also via some French philosophers (the Roland Barthes of “S/Z” ) up to our last Italian master, Luca Ronconi, and aims to consider every sentence as a painting (the raw synthesis is mine): that’s why the subtitles of the original text, in the original graphics, will remain: as a painting tag; and if a sentence comes to be a painting, a text becomes a collection, a museum. This is the moment to apologize for my English. Not for semantics (dictionaries are no merit) but for these up-and-down sentences; and all these parentheses: in Italian, I would make the effort to sculpt a marmoreal text as linear as Julius Caesar would do. In English, I suspect I am carving my wood like a barbarian. And I am sure I will fail some ‘tune’: just take for granted that I “come in peace”…

Comments.

I must admit that, for the reasons said before about sharing experimental results, I agree, at different levels, with every comment of yours, furthermore so gently expressed: I find them all reasonable and a part of myself thinks the same with all my heart: but I have to close alternatives: i.e. exclude some of them from the final cut.

I have the strange belief that every action brings some violence, to a certain degree; especially when you work on a ‘public author’; I was the curator of an exhibition for Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium (at the Genoa Science Festival, and a couple of museums afterwards) some years ago, and I was obsessed by the menace that I had fatally fallen into the abuse of such a beloved poetess – also beloved by me…

So, believe me if I say that I am not nonchalant, about Joyce. I feel the responsibility of touching others’ sensitivities; and as a stranger, even more (even with all that Trieste, a place that has to do with my family; and “Giacomo” etc.): I feel a bit like the usual Othello dealing with that English Rose named Desdemona (which, by the way, still hides that demon inside her name).

At the same time, I do not really doubt of your liberality.

To pay that farthing back for your attention, I will add some notes, with weariness and some fun, which I hope you will accept as a simple tribute to our common good.

The project. To start, it aims at reaching at least the ‘one-unity’ size of 74 minutes (a proper movie, for festivals or equivalent). Short movies do not really exist.

Then it aims at the completion of the whole soliloquy. Even better if other people would do it, rather than me. Like it was for the ‘Romance of the Rose’.

Details.

The voice-over (the male voice – mine).

Much like a complex, it is a bunch of flowers coming from various fields: mainly, it works as a trace to pace the editing.

Initially, I had used the version of Marcella Riordan, but it was sometimes ‘out of tune’ (not for her fault: in the succession of the sentences); but most of all it was simply too fast.

Mine, though provisional, serves to prefigure the final rhythm. A seat marker.

It is going to be substituted by proper recordings, either by Paola De Ghenghi (the first actress), or….

One moment. Speaking of her: without the talent of Paola De Ghenghi, I probably would not have started this project: and please believe me that I don’t lack actresses to call. Coming for free.

Back to our topic: the male voice.

My modest contribution to acting theory has to do with a shift from the usual method of identification with the role, to an effort of a sort of identification with the author; in other words, focusing on the act of primal creation, and to what could have happened then, on the author’s desk, before thinking about the role himself. The Sources of the Nile. After all, Stanislavsky was a man of the 19th century. And speaking of his epigones, they just brutally added some psychoanalysis to it, so that all those methods fundamentally remain a result of French psychology of the sixties of that century.

So, a certain number of these lines, let us say ten or little more, are intended to allow to listen to the Author’s voice, in the background. The Author, not Joyce himself. As the Narrator in Proust is not Proust himself.

Just like you would say that living in the Vatican city is not living in Italy…

In short: you are allowed to call it ‘Joyce speaking’ with some limitation, at the moment of writing.

But it is better referred to as the act of writing.

And for the ‘gender’ question: no, it was not in my intentions. For me too, Molly’s ’womanhood’ remains sacred. Some ambiguity can stay longer as referred to the universal acceptance of the human being, that metaphysical universality you talked about. Not certainly as a contemporary ‘gender claim’ at all; I agree with you: Molly is a ‘womanly woman’. It is not the right field, Molly, to discuss such an important question. It would be abuse. C.G. Jung has not been invited to this party. Yes, Lucia, the letter: but… It would be too forced, in my opinion.

That probably brings us to the topic of the choice of different Mollies: they will be five, maybe up to ten, in the end. With a primary ‘trinity’ – (at least in Theology I assume it will mean something, this articulation in different persons…). “Ach, und leider, auch Theologie”…

They are, in fact, different ‘selves’.

That notorious ‘Je est un autre’ is not news. The 20th century confirms it, anticipated by Rimbaud through to Pirandello and beyond (I know that you know it may be better than me, I am recapitulating just to avoid misunderstandings); and almost every self-aware artist since then has repeated this statement. We are multiple selves. Even from the most basic psychological and physiological point of view – not only from the ‘philosophical’ one: our brain is a modular machine… and so forth. I don’t have to reveal this to any one of you; it was just to confirm it: yes, it is all about that.

On the other hand, to have manifold faculties doesn’t necessarily mean becoming harlequinesque, most of all from a style-oriented point of view.

Starting from a secondary issue, the narrow numbers of intentions is set – on the one side – in order to avoid ‘exhibitionism’ (my personal demand: I mistrust exhibitionism in art); on another side, in order to underline the simple and great portrait of a woman Joyce put on page; a psychology almost always obscured (or should I say ‘dazzled’) in public by her carnality: because of this carnality, it is often easy to forget that Molly is a perfect character, peer to the greatest of novels ever written, and simply because of her little realism.

A miracle. I am sure you subscribe to this.

But, firstly (talking about the limited number of Mollies), in order to suggest that whenever we are many characters, they probably stand more like a ‘family’ than like a repertoire (and most of all an actor/actress repertoire: the gross myth of versatility)… At the end of the day, a hip of broken images still mirrors one landscape. A sky can be different from hour to hour, come rain or shine, but ‘Dublin sky is always Dublin sky’; and so on…

This subject perhaps introduces us to the lack of sex and other body-matters.

In an ideal completion of the opera, all the lines will be filmed, as we said. But, in that case, by other actresses (and probably other directors: even for a single line, or so I hope). ‘Sex’ tends to bring other ‘selves’ on stage, potentially much more different than the public ones; as we all know, on one level or other. And if sex, or a corporal intimacy, when written, remains a code, that embodied string will not. Incarnation is a different matter. And we can discuss it, but it stands as a postulate, at this degree of the discussion.

To be clearer, I personally mistrust ‘performance art’ too, just because of its refusal of using any codex.

An aware and shared code is the essential mark of modern art. It is its nature. The trait that produces the sense, in western art. The sense here is indeed produced: nothing really happens…

Sexual intercourse, or a ‘corporal act’ will never remain just a sign on stage. If it were so, it would mean very little before journalism, documentary: life, in a word. If I wished to meet Dionysus in person, I would look for him in Libya: in the guard room of a refugee camp. Pornography, for example, is never just a ‘representation’, despite what they try to make us think and sell us. A real knife, a loaded gun is a stranger citizen on a stage, as is real blood. Emily Dickinson is our true ‘loaded gun’. The Dead are alive, in our country. Performing a f(art), excuse me, is not ‘isolatable’ from the body; so, it is not a sign. The Body sets limits to the Language. Incarnation implicates different mathematics.

So, on page, sex is just a string of codes. In a movie, never. If the example is hard to accept, just change ‘sex’ with ‘death’: a snuff movie won’t ever be a piece of art, despite Mr. De Quincey.

(Let me add, confidentially that the same is happening in Politics nowadays, for what is now called ‘direct democracy’, a tide that is plaguing our countries. No codes. Immediateness. No mediation).

At least, Joyce thought this way. And that is for the general purpose.

I also think that representing Joyce on stage as he were a ‘cooler’ Dickens, or a sort of nobler Philip Roth, is just wrong. Molly performed ‘just as a woman like me’, is a short way (in the double meaning of the expression). Molly is a character, a game; she is more than a woman, exactly like a portrait is more than the model.

And also for balance. The ‘scandal’ – I say ‘scandal’ just to synthesize…

First of all, when Joyce wrote it, this ‘scandal’ had a major value.

In a shortened version of 74 minutes, it would be at the least too distracting. In that ideal future version (3-4 hours), it will be there but signified, not just exposed.

As Heraclitus concludes in the so-called fragment 93: “The lord whose is the oracle at Delphi neither speaks nor hides his meaning, but gives a sign”. “Semàinein”, in original. Semiotics…

“Ceci n’est pas une pipe”, of course; not direct, unless you are doing the cartoon bubble of Joyce – that is what appears to be the usual way in which literature is used on film.

Sorry: too many words. Having an extra day, I would cut more.

That… brings maybe to Editing: I have a great admiration – when welcome – to this comment too: it is the real hell, editing. The great challenge. A bet on balancing dynamics. The results are never immediate to the director: you easily get used to anything; and the second time you see it, you see it less.

A wrong edit is the mocking-billet on the director’s back, the last thing an author gets to know, as the husband cheated in those jokes: everybody can see the fact except for him: the last to know.

And, like every supposed betrayal, it is pretty hard to manage…

Sometimes I see everything wrong (for example the rhythm in the first part: yes, a bit too choppy!): but you cannot fix it and leave what comes next identical, i.e. some line following a couple of minutes afterwards. When I change that choppy thing, the scenes coming after will change their aspect. It is like a formal dinner: a dish too strong, delivered too early, or vice-versa… A matter of matching flavours, to apply the service properly or creatively … Editing a simple ‘crescendo’ is easy. But how many crescendos can you offer? Not even Spielberg (the modern Master of It), not even Lean or Fellini did everything the right way (perhaps Kubrick, but at a high price).

Editing, more than filming, is like ‘painting’. Raphael is not the best painter, technically speaking, in the history of art: but he is probably the best ‘editor’: full and void. Reds and blues. Light and dark… Voices and silence (I miss languor too, somewhere over there…).

Balance. It is a long-term art. The art that everyone is sensitive about, even if it is rarely noted. I honestly admit I am missing something at the starting, at the final, and here and there…

So, dream and not dream: the simple fact to pose this question seems very beautiful to me. It is related to the night of a work (Penelope’s work, in this case). I share the same doubt with you. Once made, your thing returns to be as it was before: not a thing of yours.

I like the two options of these: Molly’s day (by the way, I propose to celebrate it on September 8th) is a dream (after all, it is written…); you open your eyes when you exit from it. Someone said it.

I will leave it open.

Rudy. Yes, it is involved. My marginal opinion is that Ulysses has paradoxically more to do with Hamlet than with Homer. Paradoxically, I underline: I do not literally mean it. But he could not easily write a new Hamlet. And as Hamnet seems somehow the key to Shakespeare, so I assume that Rudy is represented as relevant as that other lost son – but only under the condition of being buried at the same depth (sorry for the image), to let his figure result likewise inner and crucial: crucial because inner, as a wound that the more it is deep, the less…. So, the very final frame is Rudy, as in some scenes before; but it is only if it results shadowed, covered by something more evident (Catholicism, Virgin Mary, Lunita…). In conclusion, it is not directly Rudy, but represents the same musical interval, simply on another key. So, I would be very, very

interested in the relative note “(This had (some) critics)”, to discuss it and learn from your idea about that; because everything is a proposal, not a judgment, here. Wrong sentences refine the law (Sir K.R. Popper would agree).

Father Rudolph and Stephen: not present; to come. It will be a challenge.

‘Errors’ (erratic lines): parsing doubts, and repeating sentences: Modernism.

Polyvocality (I have always been a Michail Bakhtin’s reader), fractures and deconstruction. Thank you for saying it. Yes, they are.

Personal note. In 1985, in a youth hostel in Killarney, Ireland, three guys stood, not knowing each other – nor themselves either, I guess – in the same room, reading Joyce at the same time: originality is not always a virtue of late teen-age years… my dream at the time was to film, one day or another, the 15th Chapter of ‘Ulysses’. The whole of it (!). I left acting and directing at a national degree at 30 years of age, and since then I have been asked, unexpectedly and a bit unwillingly, to teach it. Now I feel I have accomplished that task (some of my students are acting today with Paolo Sorrentino or Declan Donnellan) and I am slowly coming back to a sort of activity – this project started indeed as a teaching project in 2012.

I must add, for your eyes only, that I have so far used my profession exclusively to focus on my only need: literature.

Sincerely yours,

Roberto Freddi – Torino

P.S. many thanks also to Patricia for having put us all in contact with each other.